When you have felt under attack or unsafe, have you ever noticed that your reaction only worsened the situation? Then you might need to read on.

In this article we’re going to be discussing the huge difference between reacting and responding to stressful situations, and how we can bring our minds to a point of calm – even when our initial understanding of an inner or outer experience may be to panic. This is important for many overall health reasons.

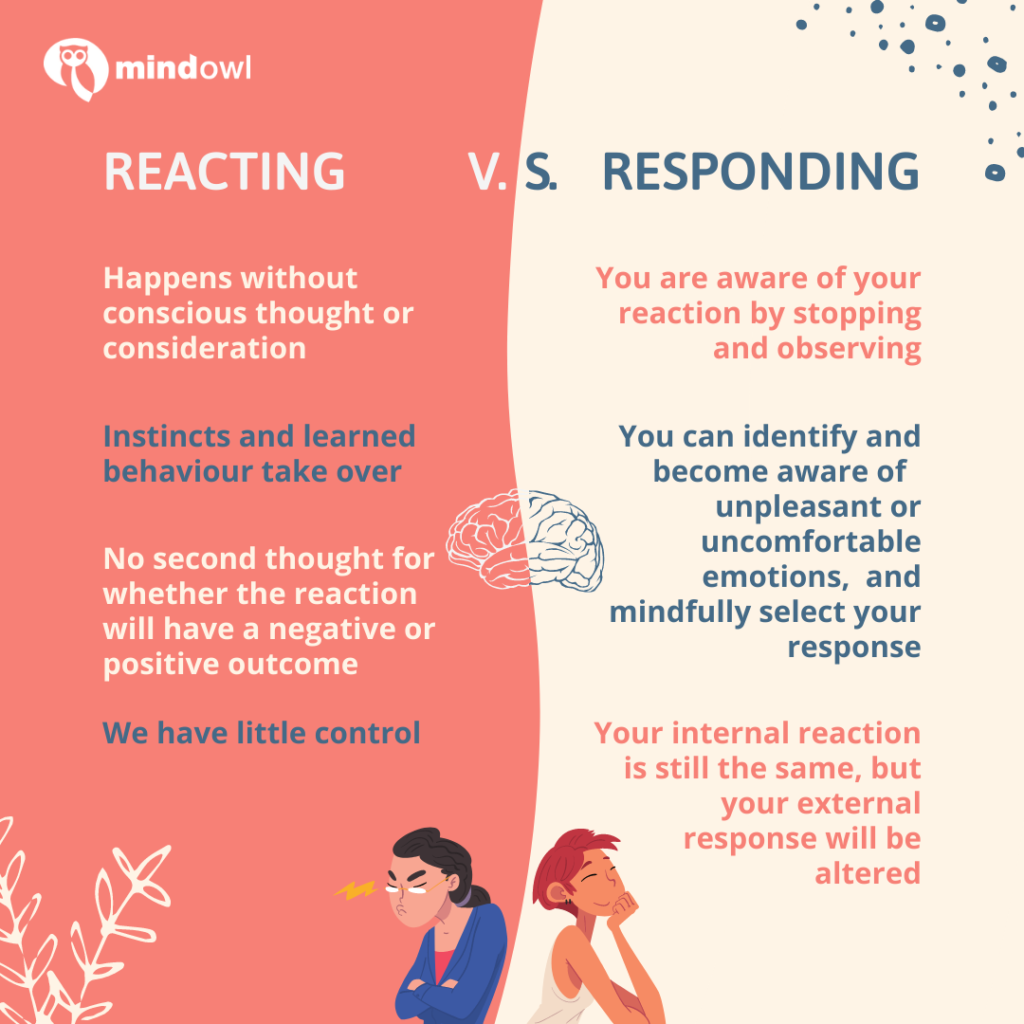

The difference between reacting and responding may not be evident to us all. If we were to analyse our knee-jerk reactions in a bad situation, we would see the harm it has to our minds and by creating relationship/task conflict in our everyday life. What this article will try to shed light on, is the importance of responding rather than reacting.

Here at MindOwl, we like to discuss awareness quite a lot. Going forward we will outline an argument for why you should try to practise awareness of your feelings and emotions. Awareness comes into this discussion when we start to define what we are doing when we react or respond.

So, why do I react?

Reactions generally happen without any conscious thought or consideration, emerging from our subconscious mind. The way we react doesn’t come from our conscious decision, but rather from our instincts and learned behaviours. We are merely allowing our instincts to take charge without considering the implications. In essence, we do not have much control, if any. But don’t worry, this isn’t as strict sentencing as it sounds.

Let’s consider an example of how we might gain a learned behaviour and how this can affect our future reactions. In the past, if we experienced an emergency situation that caused anxiety or fear – let’s say we were a child riding our bike to a friend’s place, fell off and broke our arm – it will cause us to develop a learned emotional backlash of fear. We may have felt happy and confident in our ability to get on our bike and stay upright, however, something unexpected happened and we ended up getting hurt.

What will happen next is that our brain will store that painful memory in an attempt to avoid future injury and suddenly we associate riding our bike with pain and danger. The result is that we might feel apprehensive to get back on our bikes. We will no longer trust that we are a competent enough bike rider to cycle to our friend’s house. And so we have developed learned behaviour of an emotionally negative response directed towards riding a bike. Logically, we know that just because we fell off of our bike that one time and got hurt, doesn’t mean it will happen every time thereafter.

However, our brains have developed to protect us, even when objectively we can tell that we are in no danger. The next time we are invited to ride our bike with some friends our reaction will be to panic and believe we cannot do it.

Responding – Becoming aware of our reactions

A response is very different. Rather than letting our pre-programmed behaviours take the reins, to respond we must stop, observe and become aware of our reaction and communication style. Then we can use a more rational mindset to determine the best way to advance in any current situation, conflict or task. You may have noticed that even in response, we will still experience our reactions. You will get invited out for a bike ride with friends and still feel that sense of dread, trepidation and anxiety.

So what’s the point of that?

Well, that internal reaction to something that we have been pre-programmed to fear doesn’t just disappear. We know that if we try to ignore or suppress negative emotions and thoughts then they will only get stronger.

This is exemplified by the famous White Bear experiment in which the participant is asked to not think of a white bear. Just the suggestion of a white bear imbeds that image in their mind, and when they try to stop themselves thinking of the white bear – “don’t think of a white bear” – the thought they are trying to suppress is in the instruction. Therefore, we know that it is next to impossible to suppress thoughts and emotions, and attempting to do so will only cause those thoughts and emotions to grow stronger.

Responding vs. Reacting

What we change when we are responding and not reacting is our awareness of these unpleasant thoughts and emotions, one of the functions of mindfulness. Rather than ignoring them and just going with our pre-programmed reply, we identify the unpleasant or uncomfortable emotion, become aware of it and mindfully select our emotional response. By doing this we are less likely to create a worse situation for ourselves or those around us. So our internal response is still the same, but because we deal with it differently, our external response will be altered.

For example, if you have anxiety whenever you notice a physical ache and interpret this sensation as something critically wrong with your health, you might suffer from an anxiety attack – if you react by worrying excessively and fail to recognize your thoughts and emotions rationally. And as the cycle goes, your brain will associate feeling any unknown sensation in your body with the negative experience of an anxiety attack. Therefore, the next time you feel a similar sensation your mind will instantly go into defence mode or fight, flight or freeze.

The same method applies to turning this reaction into a response. When an unknown sensation is felt and you sense your mind going into survival mode, try to identify the feelings or triggers and tell yourself that you are perfectly safe. Identifying times in the past when you might have felt similarly but nothing bad has happened is a great method for rationalising your thoughts.

Another way to look at our reaction vs response choice is to talk about the way our mind deals with challenges. This discussion is fairly similar to the previous point on learned behaviours, however, it focuses more on our attitudes and thoughts towards our abilities.

In difficult situations – so a difficult conversation, a presentation at work or even skydiving for an extreme example – how we react depends on how able we feel to handle the challenge. A challenge that we believe we are not up to without harming ourselves, failing to accomplish a goal, or embarrassing ourselves can be perceived as a threatening one by our brain. The way our mind and body deals with an emergency that we feel underprepared for is to throw us into a fight, flight or freeze mode, this is simply a cognitive function.

Fight, flight or freeze mode is something you are probably familiar with. However, if you need to see how this might manifest itself in this particular example then imagine you’re about to give an important presentation at work. A little nervousness is completely normal in an anxiety-inducing situation, for most people. You begin to doubt the success of this presentation as you get closer to the start date, telling yourself you haven’t prepared enough, didn’t do enough research and haven’t rehearsed enough. You start having visions of the ways you could mess up, convincing yourself that your peers will reject you if you don’t succeed.

In this situation, you may either try to avoid giving your presentation, give your presentation but show signs of agitation and anxiety or try to give your presentation and freeze up. Either way, you will not be receiving a “great job today!” email from your boss afterwards.

Again, if you are giving an important presentation you are going to feel a bit of anxiety and nervousness. However, if your mindset and attitude towards this challenge tell you that you are prepared and capable of being successful then you will respond rather than react. You will be able to identify these feelings of fear and anxiety, be aware of them, and respond in a way that does not give them more power.

Mindfulness to keep your cool

Current studies and a large body of literature on the subject illustrate the positive influence and effects of mindfulness training. Learning to respond and not react when you are confronted with a difficult or scary situation is very difficult. But, with practice, it is possible to reduce the amount of time you spend being reactive by mindfully bringing your awareness to them and responding compassionately.

To teach yourself a compassionate response, try to always pause the moment you feel the familiar fight, flight or freeze response.

Before you allow yourself to be overtaken by fear or anxiety, take a deep breath mindfully to recentre your energy. Label your reaction – is it fear? Insecurity? Frustration? Anger? Anxiety? Ask yourself why you are feeling this way? What triggered it? Was it this isolated incident, or did it trigger an instinctive psychological function?

Through cognitive control – asking yourself “why” – you will become more aware of your emotional blind spots. As you give yourself a moment to pause, gently ask yourself what is your goal? How you can respond in a way that moves you closer to it?

Through doing this cognitive training you will empower yourself to have an awareness of your instinctive feelings and how you can respond more healthily. Through focused attention mindfulness you will be empowered to overcome negative cognitive functions as they arise throughout the day. But do remember, recent studies in developmental literature show that control of emotional functioning improves with age. So, the more you practice using a compassionate response using executive control, the easier it will be.

I hope this article has introduced you to a new way of approaching challenges that cause you fear or anxiety. The important thing is to become aware of your emotional reactions, and put a halt to them by acknowledging their presence in your mind but not allowing them to control your behaviour and mental health through emotional acceptance. This is simply mindfulness intervention training.

The past can create learned behaviours in our minds that become preprogrammed rather than reflecting our values and goals in a situation. This knowledge won’t cure you of all future fears and anxieties, and you will still have reactive moments in your life. It does, however, allow you to assess your behaviour and begin to break down some of those learned behaviours with positive effects, inevitably resulting in a more calm mindset, more fulfilling relationships and better mental health.

MindOwl Founder – My own struggles in life have led me to this path of understanding the human condition. I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy before completing a master’s degree in psychology at Regent’s University London. I then completed a postgraduate diploma in philosophical counselling before being trained in ACT (Acceptance and commitment therapy).

I’ve spent the last eight years studying the encounter of meditative practices with modern psychology.

5 thoughts on “Respond, don’t React: Taming Stress through Mindful Presence”